The Indian Medical Association and other allopathic doctors have no moral basis to cast aspersions on Ayurveda or AYUSH companies.

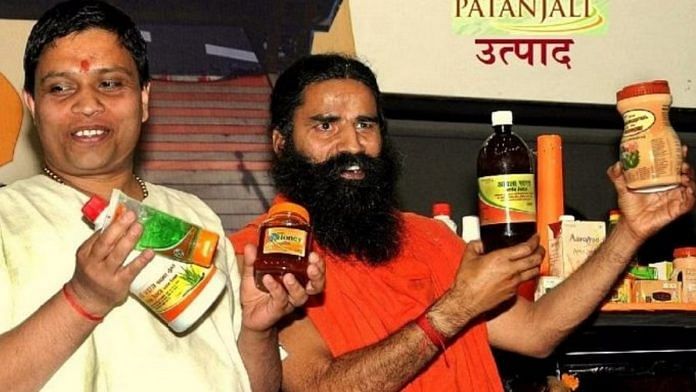

A file image of Ramdev showcasing his brand’s products | Facebook

Amid the accusations of misleading advertisements against yoga guru Ramdev and his brand Patanjali, the attention appears to also be directed toward Ayurveda as a system, rather than addressing the wider issue of transparency and ethical communication within healthcare.

In a Supreme Court petition, the Indian Medical Association (IMA), the country’s largest network of allopathic doctors, has accused Patanjali of making disparaging statements about allopathy and demanded that the brand be stopped from issuing misleading advertisements. The IMA also pointed to Ramdev’s controversial statements about modern medicine and vaccines during the second wave of Covid-19.

In this regard, the court in February pulled up Patanjali for continuing to release misleading ads despite the brand’s assurance in November 2023 that it would not do so. Then in April, the court rejected an apology from Ramdev and Patanjali managing director Acharya Balkrishna on the grounds that it was “perfunctory”.

In the ongoing legal proceedings, the IMA’s side appears strong given that the court concurs that Patanjali is guilty of misleading advertisements. However, the danger lies in conflating unethical practices with traditional medicine alone and thereby discrediting them.

Ayurveda is also important

Today, allopathy dominates global medical practice, with alternative treatments such as homeopathy used to some extent.But it has to be understood that allopathy is a very new medical system compared to Ayurveda.

In India, prior to the advent of allopathy, Ayurveda was the dominant basis of medical treatment, along with other traditional systems such as Unani, Siddha, and Sowa Rigpa. While allopathy and homeopathy now dominate here too, Ayurveda is still an important system of medicine, about which a great deal has been written in Indian literature. Information is available about many Ayurvedic experts, surgeons, doctors, and medicines.

Ayurveda offers not only information for treating various diseases but also special knowledge for living a healthy life and preventing illness. This focus on preventive care is a USP of Indian medical systems, particularly Ayurveda. In recent times, the government of India has made significant efforts for the promotion of traditional systems of medicines through the Department of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy).

However, there have been many occasions when allopathic doctors and their groups have mocked other medical systems. Organisations such as the IMA also have sufficient resources to fight legal battles. But this does not mean that allopathic practitioners are immune to perpetuating misinformation and malpractices.

Medicine and ‘moral’ advantage?

The legal action against Patanjali stems from alleged violations of the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act 1954, concerning misleading advertisements. But this issue is not isolated to any one healthcare system; it is observed across various medical practices, including allopathic medicine.

In fact, some years ago, the IMA instructedits members to refrain from advertising “no cure, no payment” or “guaranteed cure” claims, citing violations of the Medical Council of India (MCI) Code of Ethics Regulations and the Drugs and Magic Remedies Act. The directive came after a doctor couple running an IVF clinic in Mumbai had their licenses suspended for promising guaranteed pregnancy and offering refunds if treatments failed.

But even reputable institutions like the IMA have occasionally overstepped or disregarded regulations by endorsing commercial products inappropriately. For instance, in 2008, the IMA drew flak from the Health Ministry for endorsing international conglomerate PepsiCo’s Tropicana juices and Quaker Oats. Similar controversies arose in 2015 with the endorsement of a water purifier brand and in 2019 with the “certification” of a supposedly antimicrobial light bulb.

Not just this, in 2019, a report by the NGO Support for Advocacy and Training to Health Initiatives (SATHI), alleged that representatives of major drug companies bribe allopathic doctors to help them sell their medicines and other products. This later resulted in Prime Minister Narendra Modi warning pharma firms to desist from such practices.

While the court’s intention to enforce rules is commendable, the call is for a uniform and fair application of the law. Every medical practitioner and organisation, not just Ramdev, should adhere to these regulations to ensure transparency, trust, and the highest standard of healthcare communication and practice.

Last year, when the government of India made it mandatory for doctors to prescribe medicines with their generic names for the sake of affordability and access to treatment, many doctors—including the IMA—opposed it, claiming that the “drug ecosystem” was unprepared.

On the one hand, the government is opening Jan Aushadhi centres for the sale of generic medicines in large numbers and trying to tighten the rules for ethical practice by doctors and hospitals. On the other hand, the IMA and its members are not ready to give up their benefits, such as attending conferences organised by pharma companies.

In such a situation, the talk of ethics by allopathic doctors and their associations seems ridiculous.

All systems failed in Covid-19

In 2022, the IMA filed a petition in court, urging the central government, the Advertising Standards Council of India, and the Central Consumer Protection Authority of India to take action against advertisements promoting the AYUSH system by disparaging allopathic medicine. It further raised concerns about the spread of misinformation harming modern medicine’s reputation and argued that Patanjali’s advertising violated existing laws. Much of the controversy around Patanjali has centred on its formulation Coronil, which was recommended by the AYUSH ministry as a supporting medicine for Covid management.

It is well known that during Covid, allopathy, the so-called evidence-based medical system, was also proving to be ineffective. Everyone, including the WHO, was in the dark initially. All medicines were being given only on the basis of ‘trial and error’ and many had no discernible benefits. In such a situation, many Indians placed their trust in “kadha”—Ayurvedic concoctions that do not contain even a trace of allopathic medicines.

In this context, if Patanjali promoted Coronil or any other medicine and allegedly earned huge profits from it, isn’t it also true that pharma companies earned much more by selling ineffective medicines?

Despite uncertainty around the effectiveness of treatments, injections such as Remdesivir were sold at inflated prices, with pharmaceutical companies pocketing huge profits. During this time, thousands of people lost their lives in hospitals, leading to the widespread belief among the general public that it was safer to treat Covid at home.

It has to be understood that the question is not about allegations and counter-allegations, but of morality.

The IMA and other allopathic doctors have no moral basis to cast aspersions on AYUSH or AYUSH companies. The ultimate goal of all medical systems is to protect and promote public health and well-being.

While Ayurveda is based on the concept of healthy living and provides low-cost treatment on the basis of our ancient knowledge traditions, allopathy offers medicines and other therapies for many serious diseases. Both systems can contribute to public well-being. But no system has the right to claim that all others are “unscientific” or “incorrect”. The real goal must be improving public health instead of disproving one another.